The Natives Who Lived in My Area, Their Leader Chief Friday, and Their Council Tree

What Native Americans Can Teach Us in Our Churches and Public Life, Part Three

Have you ever thought about the people who lived on the land in your community before it was “settled” by whites? No matter where you live in the U.S. there is a story to be uncovered in your own backyard. It will likely be a story of conflict and displacement.

I live in Fort Collins, Colorado. The history of indigenous people here goes way back, ended tragically not that long ago, and cries out for reconciliation work. But first, a brief history.

Paleo-Indians were living, hunting and gathering in our area 11,000 years ago. Their artifacts were discovered at Lindenmeier site, a major Folsom archeological find just north of Fort Collins.

No one knows the number of indigenous people in the Americas before the 1492 voyage of Christopher Columbus. Estimates range in the tens of millions, with more than 500 tribes. Disease and violence brought on by ongoing European settlement decimated tribal populations.

The fur trappers and explorers of the early 1800s in our region not only traded with the natives, but they sometimes married them. William Bent was the best-known trader in the land that became Colorado. In 1835, he married Owl Woman, the daughter of White Thunder, a Cheyenne chief and traditional healer.

By the mid-1800s Comanche, Ute, Kiowa, Arapaho, Apache and Cheyenne all lived in and moved through northern Colorado, but it was the Northern Arapaho who lived in the Poudre River valley, which traverses through what became Fort Collins. Rivers flowing from the mountains, a dry climate, and some 30 million bison across the western plains, abundantly sustained the native people in this area. (Among These Hills, a History of Livermore Colorado)

The 1860s: A Tragic Decade for the Arapaho and Other Tribes

In 1860, the Arapaho and Cheyenne shared land encompassing one-quarter of Colorado and parts of Wyoming, western Kansas and Nebraska, as determined by the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty. The Pikes Peak Gold Rush changed everything for the tribes with a mass integration of miners and settlers. In 1861, when Colorado was established as a territory, the Treaty of Fort Wise attempted to remove several groups of Cheyenne and Arapaho to a small area in southeastern Colorado.

The majority of the Cheyenne and Arapaho did not move to the reservation, and conflicts between settlers and indigenous people continued. In my last post, I wrote about the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864 and subsequent conflicts on the eastern plains of Colorado.

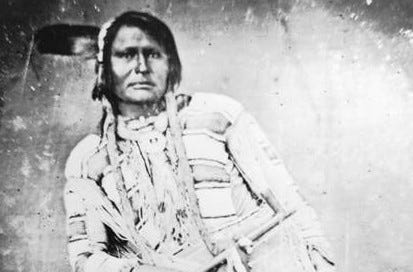

In these early days of white settlement, a band of Northern Arapaho lived in the Poudre River Valley. Their leader Warshinun, or Chief Friday, left a legacy as a peacemaker during a time of ongoing conflict during the early days of territorial Colorado and the founding of Fort Collins.

Friday had an unusual upbringing. Separated from his Arapaho tribe as a young boy, he was found by a fur trapper named Thomas Fitzpatrick who unofficially adopted him, named him “Friday” for the day he was found, and sent him to school in St. Louis. There he learned English and returning to Northern Colorado became a tribal leader and negotiator between Native and non-Native peoples.

The Council Tree

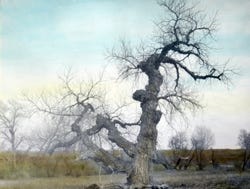

One important meeting spot for Friday and the Arapahos was a 120-foot cottonwood tree that came to be known as Council Tree. Friday simply said of the place, “We met there.” According to one early settler, because of an 1862 council held there, the land along the Poudre was given to the whites, and the government agreed to support the Arapaho living there. (See page 43, People of the Poudre, Lucy Burns)

The government failed to meet its promises to support the Arapaho. Friday had requested a reservation near the Poudre River which interfered with the intentions of white settlers who had no legal right to the land. Forced by the threat of starvation, the hostility of some local citizens, Friday and the remanent Arapaho relocated to the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming in 1870 where they settled alongside the Shoshone. (People of the Poudre gives a detailed account of the final years of the Northern Arapaho in the Poudre Valley.)

The Northern Arapaho Today

The Northern Arapaho continue to share the Wind River reservation in Wyoming with the Shoshone tribe. Life on the Wind River Reservation is difficult to this day with high rates of poverty, unemployment, violent crime and alcoholism. Pollution from uranium mining and oil wastewater harm the environment and present health hazards. See 2012 article in the The New York Times.

That said, not all Northern Arapaho live on the reservation and not everything happening on the reservation is bad news. There is a rich communal life represented by pow-wows and preservation of the Arapaho language. A few casinos have stimulated economic growth. A herd of bison are being reintroduced. And a legal effort is underway to reclaim land taken away in Colorado and to address other historical injustices.

“Once we were removed [from Colorado], they just simply started divvying up the land, creating parcels and selling it to non-Natives other interests and businesses, said Dallin Maybe a member of the Northern Arapaho who them is taking part in the just released Truth, Restoration and Education Reports. It estimates the value of homelands at $1.7 trillion.

Specific to Fort Collins, one of the report’s recommendations calls on Colorado State University to return 19,000 acres of land to the tribal nations, claiming that it was illegally taken from them at the time of CSU’s land grant. Another recommendation is that CSU and other Colorado universities do more to support native students and the native community at large.

Council Tree Revisited

I don’t have to look far from home to be reminded of the Arapaho who lived in my immediate area and the legacy of the Council Tree. Several years ago, the name of our church in Fort Collins was changed to Council Tree Covenant Church. A close by library and avenue are also called Council Tree. Locally, the name is generally associated with a peaceful gathering place. Sadly though, the name Council Tree also is a symbol of the last years of the Northern Arapaho and their forced departure from the land and life they loved in the Poudre River Valley.

By the late 1940s the Council Tree had died. Tribal elders of the Northern Arapaho still consider the surrounding area to be sacred. Just about 30 years ago some 50 people, led by Arapaho ceremonial elders, gathered for a blessing of the ground on which the Council Tree once stood.

“This place was very sacred to us, that’s where we all gathered,” said the late Crawford White Eagle, one of the elders. “[We] had our council [there]. Different bands, even different tribes. Mainly the Sioux and the Cheyenne. We loved this land, but we were pushed aside for the settlers, the miners. Places like this should be remembered, not only for the tribe but for our younger people.”

I’d like to think we at Council Tree Church could play a role in honoring the legacy of the Northern Arapaho represented by the sacred tree. A good start might be to simply acknowledge the injustice of broken treaties and the tragic ending to the life they enjoyed in the Poudre River Valley.

We also could affirm that Chief Friday as his people have noted was a peace chief, not a war chief, and as Jesus said, “Blessed are the peacemakers.”

The Imaginate Project happening this weekend at Confluence Park will feature a Blackfoot flutist and is going to recognize that the land they are gathering on was the winter home of Little Ravens band. They will also have Latina, Jazz and Blues musicians coming together as a united front of Christ's followers to bring reconciliation and healing to the pain of division and separation

I've found myself wondering, "What if we planted a new Council Tree?" To bring honor to the past and to recommit our efforts towards peace and reconciliation for the future. Invite Chief Friday's ancestors to be a part...

Thank you for your post.