What Native Americans Can Teach Us in Our Churches and Public Life, Part One

First Nations Theologians and Leaders Can Help Us Deal with the Past and the Present

One hundred years ago today Congress passed the Indian Citizenship Act — the law which granted citizenship to Native Americans in the United States. Secretary of Interior Deb Haaland, Laguna Pueblo tribe, said of the anniversary: “We have always been citizens of this continent. Our citizenship runs deep, and in spite of every Indian war, assimilation policy, and outright assault on our land, animals, and ways of life by newcomers, we have persevered.”

Just today, at Trader Joe’s, a brief conversation with our friendly young cashier revealed his Comanche heritage in Oklahoma. When I mentioned this historic day, he seemed surprised that I was aware. He reminded me that this date was just about getting citizenship and that voting rights for Native Americans weren’t fully established at the national level until 1965.

My current reflection on Native Americans was sparked by a recent visit to the Black Hills of South Dakota, including the museum at the Crazy Horse Memorial, and a stop at the Fort Laramie, Wyoming, historical site where many of the treaties with Plains Indians were made and later broken. I’ve also been reading and listening to Native American theologians, reflecting on the devastating effects of “The Doctrine of Discovery.”

How the West was ‘Won’

It’s important to say upfront that many indigenous theologians point to the Catholic church’s “Doctrine of Discovery”, papal declarations from the 1400s. “It’s a worldview that a certain group of people based on their religious identity (primarily Western Christendom), had moral sanction and the support of international law to invade and colonize the lands of non-Christian peoples, to dominate them, take their possessions and resources and enslave and kill them,” according to theologian Kelly Sherman Conway, a member of the Oglala Lakota Nation.

This view gained traction in the early settlement of the country — from the Puritans in the colonial era to the westward expansion of the U.S. in the 19th century. Henry Clay, U.S. secretary of state from 1825-29, reportedly stated a view held by many white settlers, “The Indians’ disappearance from the human family will be no great loss to the world. I do not think them, as a race, worth preserving.”

Like every other white family who traveled west, my Protestant ancestors settled on land that First Nations people had lived on for thousands of years. My family on my dad’s side moved west from New York to Ohio than on to Minnesota, Iowa, South Dakota, Nebraska and Colorado. We now live in Fort Collins, Colorado, which has roots in the fort established here during the “Indian Wars” of the mid-1860s.

The Doctrine of Discovery intertwined with white superiority resulted in broken treaties that remain painful for many Native Americans.

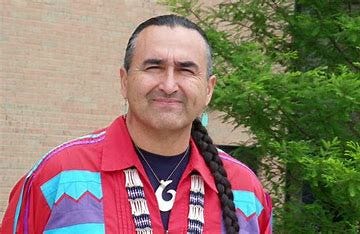

Richard Twiss: One Church Many Tribes

“Broken covenants have caused a huge chasm of distrust and great animosity in the hearts of native peoples,” wrote theologian Richard Twiss, a member of the Rosebud Lakota/Sioux tribe of South Dakota. Based on the biblical concept of covenant, the U.S. “may very well be held to give an accounting for her broken treaties with the First Nations people of North America.”

Twiss, who wrote “One Church Many Tribes” and “Rescuing the Gospel from the Cowboys,” passed away in 2013. He was a powerful prophetic voice in the evangelical world. Twiss believed:

It was important to express his faith in Christ in the context of Sioux culture, which included worship at pow-wows and sweat lodges.

“As Native people we must also own up to the fact that our people committed many heinous acts of violence against innocent White settles and homesteaders.”

The indigenous people of the land are some way “inseparably linked to spiritual revival in the Americas.”

As disciples of Jesus Christ, “we can step into long-standing deadlocks as agents of healing between Native and Anglo cultures.”

The biblical practice of intercessory prayer where we identify with the sins of our ancestors “has incredible potential to bring revival and healing to all of the inhabitants of America, but it has remained a neglected truth.”

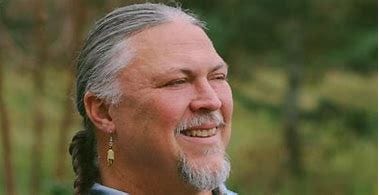

Randy Woodley: Steps Toward Reparations

Randy Woodley is a Cherokee theologian, farmer, and professor at Portland Seminary. He emphasizes a value shared by a lot of tribes: harmony with God’s creation and restoration of broken relationships.

“What White Western folks must do, both structurally and individually is to heal the relationships between themselves, Creator, the land, and the local Indigenous people,” Woodley wrote in “Indigenous Theology and the Western Worldview”.

“Second, we need to lament together because that is part of becoming a community. Confession in the public square speaking truth to power. Allow time for it to sink in and then, very importantly, reparations need to be made.”

What do reparations look like? “It might mean remuneration of money in some places. It might mean land in others; it might mean both or other creative things.”

Broadening of World Views

Native American theologians resonate at this time of extreme political polarization. They can teach us that we are all children of one Creator and that we should treat one another as such. They can also lead us toward a better relationship with the land, animals, flora and fauna — as they view all of life as sacred and connected. They can help us to see that within the confines of our own cultures, our views of God can become much too small.

In my next blog posting, I will dive more into the Native American history of my own state of Colorado, and how a local Native American theologian became an agent of truth and reconciliation.